Most people, even if they do not collect antiques or have any interest in folk art, have heard of “ships in bottles,” have marvelled at the ingenuity of the carvers and wondered at the process of building the ship through the narrow neck of a bottle. Few people, however, realize that there are other forms of folk art in bottles, forms which are widely repeated and which have many common features.

Other subjects carved and fitted into bottles include bar scenes, chairs, framed photographs and tintypes, birds, fans, tools, yarn winders and niddy-noddies, wishing wells, and crucifixions. Often called “whimsy bottles” because they were made for no apparent purpose other than for the fun and challenge, they clearly have their roots in German and Slavic folk art tradition. This tradition is known to go back at least into the early eighteenth century.

Crucifixion bottles

Fans

Chairs

Yarnwinders and spinning wheels

Ships

Wishing wells

Photographs and pictures

Scenes, and buildings

Tools

Miscellaneous

They were made by the same kinds of people who whittled to pass the time: sailors, prisoners, model-builders, and people who enjoy working with their hands.

Who? When? Where? To be perfectly honest, we don’t know a lot about the people who made these clever carvings and put them into bottles. Only about ten percent are signed or dated, but where they are found often provides clues for those willing to look for them. Except for one bottle I own that was made about ten years ago by a woman artist, all of these bottles seem to have been made by men: Men who have time on their hands, skill with these hands, and enjoy a challenge. Possibly prisoners or hobos. In the United States, by far the greatest number of these bottles have been found in the midwest, from Pennsylvania to Kansas and further north into Michigan and Minnesota. The dates on American bottles range from the middle of the nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century.

More than one! In several cases, we know the same artist made more than one bottle of similar design, even when we don’t know his name. Examples of multiple bottles by the same artist are: (a) The “Book and Hand” artist, who made two of the wishing well bottles and several “miscellaneous” constructions; his stoppers were always elaborate, sometimes being a carved hand holding a book. One of his has two hands coming up, holding the book. (b) A carver of exquisite crucifixes, possibly made in Connecticut. Each of the five at this website is linked to the other four. (c) H. H. Hutchins of Maquoketa, Iowa, who made yarn winders in 1914-1915. (d) Adam Selick of Pennsylvania, who built structures like wishing wells without the well, and decorated them with carved birds and wooden fans. (e) An artist known only by his initials, M.H.L., who made chests of drawers in bottles. He is known to have made at least four and possibly more, all in 1918-1919. (f) The “Soldier’s Home” artist, , probably from Indiana or Ohio, who made tiny ships in small, flat bottle flasks. (g) The most prolific known bottle maker, Carl Worner, has an entire page on this website. So far we know of almost fifty bottles he made, but only eighteen are pictured here. There are many examples of two bottles clearly made by the same maker, being nearly identical in design.

Why? Some bottles were made as memorials, either to a deceased person, or for a wedding or birthday. One bottle, built into a slate-based lamp, commemorates the Unknown Soldier of World War I. Another apparently honors the founding of a sanatorium in Hungary. Some were made for gifts, such as at least two of Adam Selick’s bottles. Carl Worner made most, if not all, of his bottles in exchange for food, clothes, shoes, lodging, and above all, drinks at the local tavern. But most of the bottles do not have a known reason to exist. They were just made for the fun and challenge, or to pass time. The makers of the crucifix bottles were undoubtedly making a devotional statement by carving these powerful scenes and putting them safely in a bottle.

Categories. The most common categories of bottle designs are ships, crosses (and crucifixions), chairs, yarn winders, fans, and tools. Less common are photographs, wishing wells, spinning wheels, and scenes (not counting the prodigious output of one artist, Carl Worner). Some are truly one-of-a-kind in design, like the American flag all woven out of beads, and defy categorization. Rare bottles contain mechanical assemblies that turn through a crank inserted through the stopper. There are examples of mechanical bottles from Germany, but one at this website, containing a spinning wheel, was made in America in the 19th century.

Ships in bottles were undoubtedly made before the twentieth centuy by sailors to pass the time on board during long vogayes. In the years after the age of sail, some effort was made to assure this art was not lost. Articles and books have been published showing how ship models were constructed in collapsed form outside of the bottle and raised by pulling special threads. In 1930, the magazine Popular Science, sponsored a ship-in-bottle contest and got many beautiful entries, most of which were made by hobbyists. Quite different from the traditional bottle ships, the “Soldiers Home” ship bottles are small (4.5 inches across), flat circular flasks with a small ship inside, not embedded in “water”; they have something hanging from the stopper, often a lifeboat. Five of these bottles are shown on the Ships in Bottles page of this website. At least ten are known to exist, many having been found in Ohio and Indiana. One contemporary shipbottle artist, David Smith of New Brunswick, has a website showing examples of bottle ships, including a history.

Another form of bottle is one whose form is clearly traceable to Germany and eastern Europe: the crucifixion bottles. Three in my collection were found in flea markets in Budapest and have dates as recent as 1949 and 1961. Many of the crucifixion bottles were found in western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio where there are large populations of Slavic people who came to mine coal in these regions, but others have turned up in Kansas, Iowa, Missouri and the upper midwest. While I am guessing that the first makers of these bottles were Roman Catholic, I would also guess that many made in this country were made by Protestants. The earliest dated example I have was made by W. A. Poole of Reading, Pennsylvania in 1886. Poole is not a Slavic or Germanic name, so it is clear that in this country, the art form spread to Americans of other roots.

Crucifixion bottles have many features common to most of them: besides the cross, there are almost always tools which are mentioned in the Gospel accounts of the passion and death of Jesus. Most common are a ladder, a spear, a long stick with a sponge on the end, hammer and nails, and sometimes a shovel. Other common objects are the cock that crowed when St. Peter had denied Christ three times, a flail, dice representing the soldiers who cast lots for Jesus’s cloak, a chalice, and a crown of thorns. Often there is a small banner with “INRI” on the cross, and often there is a carved body of Jesus on the cross. In the more elaborate scenes, there are soldier guards and/or the two thieves on smaller crosses. Some of the crucifixion scenes are painted, but most are not. Sometimes the figure of Christ is a cut-out from a picture. In rare cases, the bottle stopper is carved in the shape of a cross or steeple. I have one bottle with no cross, but it has tools and a sign with the letters INRI.

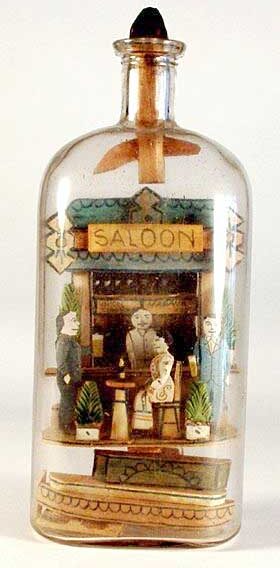

Bar or saloon bottles are bottles with scenes of a saloon built inside; although all of the examples known are American from the 20th century, I suspect they come from the same tradition that would put a scene from a mining operation in a bottle. Most of the exampes were made by one man, Carl or Charles Worner (sometimes signed as Warner), whom I believe was a German immigrant to the U.S. and who lived and worked in a number of American cities between 1900 and 1920. His bar bottles usually have a sign or note in them to “Find the Missing Man.” The scenes contain a bartender and customers at the bar, as many as four or five; but the “missing man” is below the floor in the “crapper,” which is usually an open three-sided niche with a carved or painted figure inside. Two of Warner’s bar bottles were constructed in large seltzer bottles and have not one but two men below the main floor using the men’s room. Worner also made bottles containing shops, families in their homes, possibly a clock, and at least one crucifixion.

Bottles containing photographs or pictures are less common and feature a wooden frame which is constructed inside the bottle with pegs and mortise-and-tenon joinery. At least one in my collection was made to commemorate the death of the person in the photograph, and one is an elaborately framed religious card.

The simplest bottles often contain tools, almost always including a sawbuck and saw. One of these was signed with a note by the artist that it took him eight hours to make it.

Another simple subject is the yarn winder or “niddy-noddy”, a vertical shaft with crossbars at top and bottom; sometimes they have full crosses, sometimes multiple sets. They are usually wound with yarn, string or thread. An example of a very small one is at the left. One man who made more than one yarn-winder bottle was H. H. Hutchins from Maquoketa, Iowa. He signed his with the date he made them, and his date of birth: 1839.

Spinning wheels are a related subject. A beautiful example, not in my collection, contains a fully-threaded loom and a china-head doll at the loom. It fills the bottle to the full capacity, and the doll’s china head had to be filed down to squeeze it through the bottle neck. I have heard of two or three others like this, including one with two looms and two dolls. At least one spinning wheel bottle has a paper label, explaining that the bottle was made by a prisoner in the Mohawk Valley (New York) prison in the 1860’s. The earliest known bottle contains a stocking weaver and stocking loom. It was made in Germany in 1719.

One of the commonest forms is the bottle with a chair in it. There is evidence that this form was taught in an IOOF Home in Liberty, Missouri; several have been found with dates from the 1920’s and IOOF Home on them, usually with only initials of the men who made them. The seats or backs of the chairs are usually woven in thread or yarn. Someone told me that the chairs were made outside of the bottle, including the weaving of the seat and back; then the stretchers were taken out of the legs and the whole thing stuffed in through the neck of the bottle. Then, inside the bottle, the stretchers were pushed into waiting holes in the legs, pulling the entire chair straight. This would only work if all four legs of the chair could be put into the bottle at once; I have seen several chairs which could not have been built like this.

Another common design was the fan; fans were made from thinly shaved wood, placed in the bottles while closed, and then spread open, sometimes woven with ribbons. The type of fan is still seen in Scandinavian folk art. One artist who specialized in bottles containing fans was Adam Selick from Pennsylvania. One owner of one of his bottles said he came from Emporium, PA, in the north central part of the state. He may have worked on the railroads. Most of his dated bottles are from the early 1890’s, and he was not found in the 1900 census of Pennsylvania. He made bottles for other people, celebrating perhaps a wedding or anniversary. His bottles contain a structure of an arch or four-posted frame, with fans and carved birds on the structure. A sign near the top would have the name of the people for whom the bottle was probably made.

Other bottles are exceedingly complex, such as the bottles containing buildings. One of these, which is not in my collection, was a large apothecary bottle containing a fort, people, and German flags on all sides. I have three examples of houses built inside a bottle, one just made of thin strips of wood; another which fills a square gallon jug, having inset mica windows, a double front door of wood, and a full front porch; and the third which doesn’t feature the house as much as the incredible whittling skill of the artist: it has a huge stopper, several “whimsey chains” AND an elaborately dovetail-constructed and carved house.

The stoppers are often works of art as well as the contents of the bottle. Some of the crucifix bottles have elaborate steeples for stoppers. As mentioned above, one artist carved elegantly cuffed hands holding up a book, and the house bottle mentioned in the previous paragraph has the most elaborate stopper all whittled from one piece of wood.

Stoppers are frequently anchored in place with a cross-piece that must be pulled through after the stopper is in the bottle. As a demonstration of the ingenuity of the artist, there are sometimes pegs, in addition, going through the cross-piece and holding it in place. Frequently, the appearance that the cross-piece goes through the stopper is an illusion: the cross-piece was actually two separate arms, threaded into a hole running the length of the stopper and pulled up tight through the top of the stopper. Then a knob was glued on (or in another case, black wax poured in). Carl Worner made many stoppers this way, as is described on one of the Worner bottle pages.

It is my hope that by posting this brief article and accompanying pictures that I will eventually hear from someone whose father or grandfather made bottles like these, helping me learn more about their origin and tradition. If you are a collector too, I would love to hear from you. If you would like to send pictures and have me add your bottles to this website, I would be honored to do so. And of course it goes without saying that I’m always looking for new ones to add to my personal collection.